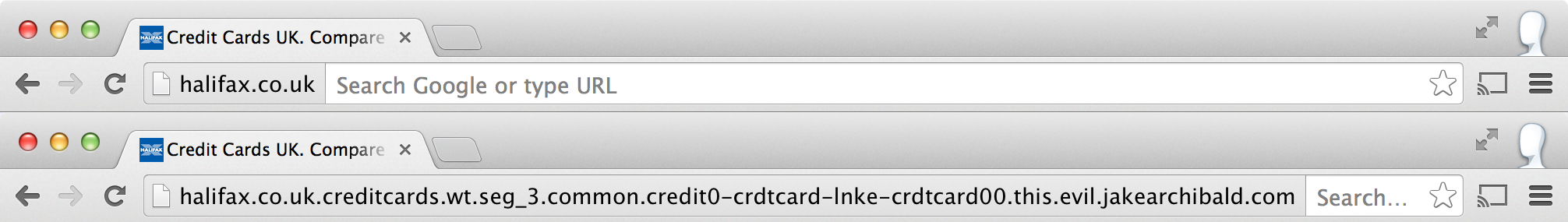

Last week, there was a fair bit of furor when Jake Archibald wrote an article1 describing an experimental feature in Chrome that hides all but the domain name of the URL you’re on. The idea is very similar to what already happens in the iOS 7 version of Safari: once navigation is underway, the URL is hidden and only the domain name is visible in the location bar. If you want to get to the full URL, then you either click or set focus back to the location bar (in Chrome, you click the domain name).

I’ll admit, the first time I encountered this behavior in iOS 7, I was a bit surprised. I quickly came to not only understand it, but also appreciate it. I’m able to tell at a glance what site I’m on and I can easily get to the URL if I want it. In the meantime, it’s a nice, clean interface that doesn’t disrupt my usage pattern.

The more I thought about it, the more I realized that this move was not only okay for the web, but it is the next logical step in a process that has been ongoing for sometime now.

We don’t own the web

We geeks tend to forget that we don’t own the web. The web is not just for us. We are its caretakers. We groom it and coax it to grow in certain directions. The web is for everyone, that means geeks and non-geeks alike. And whether we like it or not, there are for more non-geeks than there are geeks in the world. The grandparents and parents, the barely computer-literate middle-aged folk, the kids who don’t really know how to speak yet. The web is for all of them.

If you look back at the history of the internet, you’ll see evidence of this from its early days. There was almost always a push for average folks to be online. America Online and Prodigy grew to be successful because they hid all of the ugliness of the internet at that point in time. Gopher and FTP and even email, to some extent, were hard for people to use and understand. Online services that abstracted away the geeky parts flourished.

The web came after that as a way to continue the forward progress. Those online services represented lock-in, and the web was a promise of unfettered access to all of the information available online. It succeeded because it replicated the most consumer-friendly parts of those online services (embedded images, simple click-to-navigate interactions, and so on).

However, the web of the 1990s was still hostile to people who weren’t tech savvy. It was filled with potential hazards at every turn, from sending credit card information in plain text to email phishing. The consumers of the day fell victim far more frequently than we do today for several reasons: the knowledge of what was good and bad, what was useful or useless, was only available and understandable by geeks. Average people were lost.

Goodbye protocols

About ten years ago, I was showing a teenager something online when he asked me a startling question, “Why are you typing ‘http://’?” I told him that this specified the protocol that I was using to retrieve information from the internet.

“No,” he continued, “I mean why are you typing it? The browser just adds it for you when you hit Enter.”

Was it true? I tried it. Yes, he was right. I explained to him that “when I was his age” we had to type the full protocol into the browser or else it wouldn’t work.

“That’s dumb,” he replied.

He was right. It was dumb to type in the protocol when most of the time it was the same. So browsers changed to insert the protocol for you automatically. No one types “http://” anymore because it’s another thing you can easily get wrong and the average person wouldn’t understand what went wrong. What’s a protocol anyway?

These days, browsers have more or less done away with protocols altogether. There are really only two that are of consequence for end-users: “http” and “https”. And when you come down to it, all an end-user really needs to understand is that one is secure and one is not. The best way to show that is through some kind of imagery and/or color change.

Most browsers now use colors and lock icons to indicate the level of security employed by the domain. For example, Internet Explorer 11 uses green and a lock icon to for extended verification certificates. So what will people notice? The protocol or the visuals?

Goodbye email addresses

Email addresses are fairly simple, and you’d be hard-pressed to come up with a simpler alternative. Yet, how many email addresses do you know by heart these days? I know my mom, my dad, and myself, and that’s only because I set all of them up. I have no idea what email address my friends or colleagues use, even my brother’s email address is a mystery to me. Why is that?

Because email addresses represent routing information, and when I’m writing an email I’m not thinking about routing information, I’m thinking about the person to whom I’m writing. Email clients know this and so they will automatically look up email addresses based on the name you enter.

Gmail, for instance, shows every email address matching a given name. When you’re done typing the name, only the name remains in the To field (unless you have multiple email addresses for the same name, then it shows the email address as well).

The truth is, the actual email address is usually unimportant. All we really need is to be sure the message is going to the correct person. We rely on contacts lists to keep track of email addresses that we need and look them up as necessary. It’s nice that we can easily share that information over the phone with a friend, but then that friend likely adds it to a contact list under the person’s actual name as well.

Aside: goodbye phone numbers

As a brief aside, I liken email addresses to phone numbers. At one point, you absolutely had to memorize phone numbers to have a pleasant experience. It was horrible needing to dig out your personal phone book or, heaven forbid, the white or yellow pages to look up a phone number. So, we all walked around with a bunch of phone numbers in our head to make the process simpler.

With the popularity of mobile phones, however, we have largely contributed to the demise of the phone number. Phone numbers are now things you don’t even need to know – they are stored in your phone and used by telling the phone who you want to call. It’s the same mode of operation as email. Tell the device who you want to contact and it will do you the favor of using the correct routing information.

Some would argue that phone numbers have important information. In the United States, phone numbers are made up of a three-digit area code, followed by a three-digit central office number, followed by a four-digit station number. The area code tells you not only what state the phone number resides in, but also the part of the state. The central office number maps to a city. So in a sense, you have a ton of geographic information encoded into the phone number that makes it possible to figure where callers are located.

Of course, cell phones changed all that. If you grew up in one state and moved to another, you might keep the same cell phone number. Then you have a Florida number while living in Kansas. The information encoded in the number is no longer relevant or useful other than as routing information.

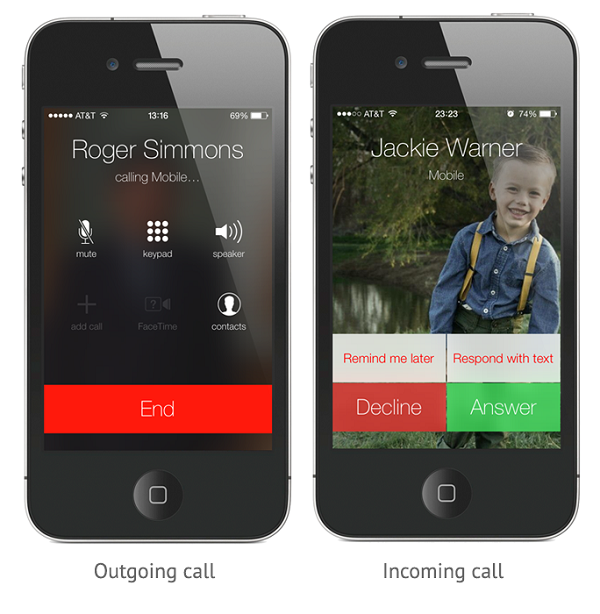

These days, I know four phone numbers by heart: my parents’ number, my home phone, my cell phone, and my mom’s cell phone. Dad’s cell phone loses out, and my brother? Not a clue. And I’m okay with that because I know that I don’t actually need that information in my brain. In fact, most smartphones today don’t show you the phone number being called unless there’s no name associated with it.

And yet, people rarely freak out when they can’t see the phone number of the person they’re talking to. Why? Because this routing information isn’t necessary to the experience.

If you want to share someone’s number, then you might actually look it up and repeat it to someone else. Or you might just share the contact using your phone. Either way, the sharing experience is pretty easy before the phone number resorts to routing information in someone else’s phone.

Goodbye URLs

And so we come back to the humble URL. What most geeks seems to miss is that non-geeks rarely use full URLs outside of sharing. URLs act, essentially, like phone numbers. People don’t need to know that they exist at all in most cases. I learned this by watching my dad use the web one day many years ago. I instructed him to go to boston.com, at which point he opened up his browser (which defaulted to Yahoo as its search engine) and typed “boston.com” into the search box. A light bulb went off in my head: he doesn’t distinguish between domain names, URLs, and search terms. To him they are all the same, just stuff you type into a box to get to see what you want.

These days, dad is a lot more savvy, but he still doesn’t use URLs. Anytime he goes to a site that he wants to remember, he creates a bookmark for it. Then, the next time he wants to view the site, he opens up his bookmarks and clicks the title of the thing he wants. Yes, it would be faster for him to type “boston.com” when he wants to go there, but that’s not the way he thinks about it. He wants to think about the thing to read and not where it’s located. The URL is just routing information to get the information. I encourage you to watch your non-geeky friends or family members use the web for a while.

Remember, most of civilization is made up of non-geeks who just want to find the stuff they want and get on with their lives. They don’t care if they get there by URL, by clicking a link, by search, or by using a bookmark. Whatever is easiest for them will work.

The one spot where URLs get most of their face time is in sharing, and even that continues to change. There are so many ways people share links these days. Facebook doesn’t show the URL in shared snippets. Twitter obscures the URL. News articles have Share and Like buttons everywhere. iOS has a share button that copies the URL to the clipboard without you seeing the URL first. URLs have been on the way out for a while.

Most end-users don’t understand URLs any more than they understand phone numbers. It’s a bunch of characters that refer to something. Why does it have this particular format? Who cares! It means nothing to most of the world.

Conclusion

Is Google trying to eliminate URLs from the web? Of course not. URLs are just as important to the web as phone numbers are to the worldwide telephone system. What they’re trying to do is to relegate URLs to the same level as protocols, phone numbers, and email addresses, which is encoded routing information that most people will rarely use in its raw form. If you really want it, it’s there behind a click. You might even consider that an “advanced” use case targeted at geeks.

I would go so far as to say hiding the URL most of the time is the next logical step in the consumerization of the web. We’ve already started down the path of hiding implementation details from end users, and that’s a good thing because the web is for everyone. You shouldn’t need to understand what a URL is or how it works in order to use it.

Who knows, at some point in the future, we might all look back and laugh at how silly it was to need to know things like email addresses and URLs at all.

- Improving the URL bar by Jake Archibald (jakearchibald.com).